GORDON BURN WAS an award-winning novelist who started by writing about the world he knew. He was born in Newcastle upon Tyne, the only child of a mother who worked at Binns, the city's department store, and a father who was a paint-sprayer. He had an outside lavatory, an uncle who kept pigeons and a regular place in the teenage queue for football stars' autographs outside St James's Park.

Calling himself "keen but clueless" at primary school, he nonetheless leapt the all-important hurdle of the 11-plus and landed safely in a grammar school, the great social escalator of the day. He was an entranced attender at Mordern Tower, a medieval turret in the remains of Newcastle's walls which was turned into a centre for readings and 1960s "happenings" by Tom and Connie Pickard, poets, writers and general activists.

Burn wrote later in the Guardian newspaper of how "we nervous grammar-school boys (never more than two of us) were exposed for the first time to mad riffers and homosexuals and junkies ... It is impossible to overstate the impact the Mordern Tower had on me as a diligent, booksniff sixth-former". His other crucial lift came from great good fortune; one of his cousins was Eric Burdon, who shot to fame with The Animals in 1964, singing on numbers such as The House of the Rising Sun and We've Gotta Get Outta This Place.

As a student, Burn liked to travel cheaply in the US and spent a memorable summer on tour with The Animals and with Burdon in Los Angeles. Back in Newcastle, he was turned down for a traineeship by Thomson Newspapers. Instead he sold a self-initiated interview with an Newcastle artist to the local newspaper, it was picked up by the Guardian. Thus he had got his break into the nationals.

Burn became frustrated quite early on in his career by the limitations of the shortish newspaper and magazine pieces that British editors tended to commission, and took his inspiration from the US. He embarked on his first book, Somebody's Husband, Somebody's Son, with ambitions for it to be a definitive, meticulously researched, literary account of the life of Peter Sutcliffe, the Yorkshire Ripper, in the mould of Norman Mailer. The finished manuscript was acclaimed as being exactly this, and it remains a classic text.

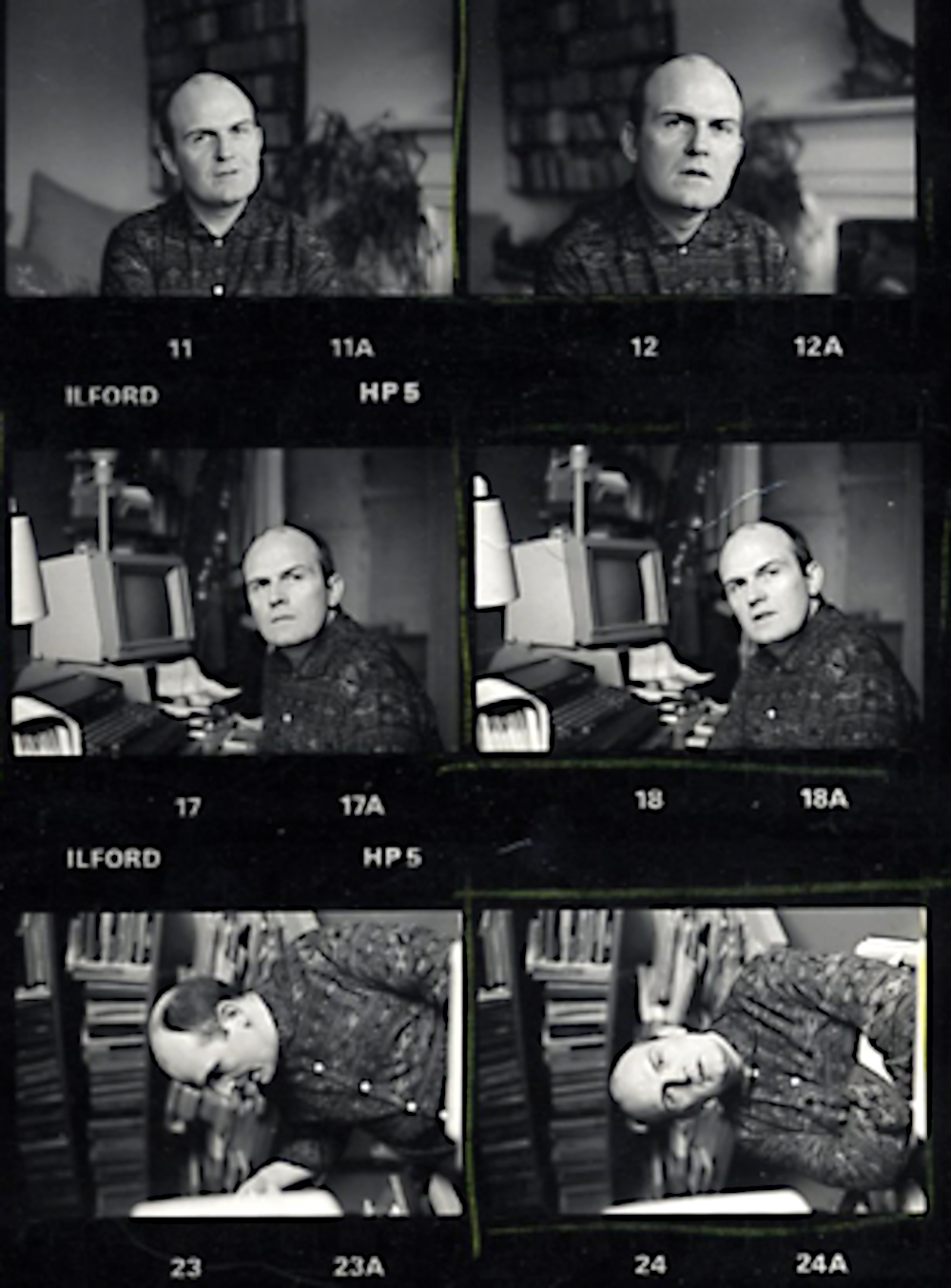

Gordon Burn went on to write himself into a highly distinctive place in modern British literature, covering a wealth of subjects in his books and journalism but avoiding all attempts at pigeonholing. He was respected as a serious researcher of notorious crimes, an analyst of celebrity disintegration and an authority on contemporary art. Terse via email, charming in person pharmacie hommes, he left those who encountered him thinking: "Is he literary? Or is he artistic?" and, most frequently, "whatever is he going to do next?"

Burn was taken ill in 2008 with diverticulitis and diagnosed with bowel cancer in May 2009. He died on July 17 2009. He was 61.

'Burn left those who encountered him thinking is he literary? Or is he artistic?' and, most frequently, 'whatever is he going to do next?'

'You couldn't get away with anything when he was around. He would come up to me and say, "You've run out of ideas, your girlfriend's going to leave you" at the slightest thing...If he thought I was slacking – he would just go for it: "You've sold out. It's over." He really gave me hell and that was one of the things that was brilliant about him'

GORDON by DAMIEN HIRST

Gordon had that brash, creative spirit that northerners have. I liked him from the first moment I met him. As far as I can remember, that was at the Saatchi gallery when it was in Boundary Road in north London. He was there to write a piece about Rachel Whiteread. I invited Gordon and his partner Carol to dinner at the place I was sharing with my then girlfriend Maia (now my wife). We got on like a house on fire, because we both liked drinking and art.

To be honest, it was more because I like northerners. I mean, I'm from Leeds and Gordon was from Newcastle, and I love Geordies. When we met, I hadn't read any of his books. Since then, I've read that great one he wrote, Pocket Money: Inside the World of Snooker, and Somebody's Husband, Somebody's Son, his book about Peter Sutcliffe, the Yorkshire Ripper. In fact, I've read all his books. I really do think he was the greatest writer, the best writer of our generation on art. It was because he was a novelist that he was so good: he brought something else to the table. There is so much bullshit and art-speak in the art world, it drives me nuts. Gordon cut through all of that.

He may have been seen as the YBAs' champion by the media, but to us he was very tough and challenging. It was real no-nonsense stuff; you couldn't get away with anything when he was around. He would come up to me and say, "You've run out of ideas, your girlfriend's going to leave you" at the slightest thing. You knew half of it was tongue-in-cheek, but even so: he was good at that. It's funny, because he was quite a shy guy at heart, but if I was slacking – or at least if he thought I was slacking – he would just go for it: "You've sold out. It's over." He really gave me hell and that was one of the things that was brilliant about him.

The first time we did an interview it was for a newspaper, I think. It was similar to the piece he had done with Rachel Whiteread. For some reason, we just carried on, I suppose because they were good fun to do. We just drank and hung out, and he got things out of me because I felt relaxed. At some point, I can't remember when, we got an advance from the publishers Faber & Faber, so we tried to be more serious about it. We would shut ourselves away until we felt we had something good. The interviews were published as a book, On the Way to Work.

I wouldn't go as far as to say we were like David Sylvester and Francis Bacon, but if anyone was a candidate for that kind of relationship, then Gordon was because I talked more openly with him than with any other interviewer. When you are an artist, you need someone who is prepared to dig a bit deeper to try to uncover what the fuck is going on. For me, that was Gordon.

The last interview we did was only two weeks ago. We had just started doing them again. I had stopped drinking, I have done for a while now, so we thought we would go back to the interviews, pick them up again and see what had changed. Gordon only agreed to do it after I made the diamond skull, For the Love of God. Gordon loved that piece, and he used it on the front cover of his recent book, Born Yesterday: The News as a Novel.

I had been trying to get him to do more interviews for ages, but whenever we met he would always say: "I think we've done all that, haven't we? We've seen that movie." But after the diamond skull, he said he thought we should do another interview. I think the skull excited him again. It's true that we both had morbid interests, and the subjects we worked on kopenpillen were about the dark side of life. But as an artist, you get involved in that – in order to make the bright side brighter. I think that's what Gordon was doing with his writing about murderers. I don't think we were morbid. I'll always consider him an artist. Perhaps that's why we got on so well.

Damien Hirst, 2009